When President Joe Biden delivers his State of the Union address on Tuesday with new House Speaker Kevin McCarthy sitting over his shoulder, looming between the two will be a possible standoff over raising the federal debt ceiling.

The management of how to increase the borrowing limit, which the Treasury Department has indicated will need to be done as soon as June to make sure none of the federal government’s bills go unpaid, is shaping up to be the first major obstacle that McCarthy and Biden must work together to overcome.

The conflict, along with the potentially calamitous economic consequences of a debt default, will no doubt color some of Biden’s remarks on Tuesday as he looks to reassure the 53% of Americans who are “very” concerned about that outcome, according to a new ABC News/Washington Post poll.

Biden and McCarthy agree that the nation cannot default on its debt.

But with the Treasury already using “extraordinary measures” to keep the United States out of the red, that’s about all they agree on.

Now that Republicans narrowly control the House, raising the debt limit cannot be accomplished without GOP votes, giving McCarthy increased influence over negotiations, if he can wrangle his conference. But McCarthy captured the gavel in the House only after a protracted speaker election that required him making concessions to the right wing of his party.

Many of those members see a debt limit hike as a powerful bargaining chip in their efforts to slash what they see as out-of-control federal spending. McCarthy has taken to their position.

The speaker looked to preempt the president’s State of the Union speech in remarks on Monday night in which he outlined what he saw as the major risks the nation faces by failing to cut its spending. He described the $31.4 trillion national debt as the “greatest threat to our future.”

Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., meets with reporters at the Capitol, Feb. 2, 2023, in Washington.

Jose Luis Magana/AP

“President Biden wants Congress to raise the debt limit yet again … without a single, sensible change to how government spends your hard-earned money. None. Does that sound responsible to you?” McCarthy said. “What Americans want — and what Republicans are fighting for — is a responsible debt limit increase that puts us on a path towards a healthier economy.”

But that’s a nonstarter for the Biden administration, which maintains that the debt limit must be raised without any political negotiation or bargaining, as has been done under both parties over many years.

“It’s just that simple. There should be no hostage-taking here. There should be no attempts to exploit the debt ceiling or to leverage it,” White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said at a briefing last month.

Biden has also pushed McCarthy to “show me your budget” — a call for the Republican speaker to outline exactly which cuts to the federal budget he’d like to see made in exchange, given his criticism of federal spending.

McCarthy has yet to present such a budget and his remarks on Monday night again lacked details about what sorts of specific cuts he’d call for.

And while McCarthy has publicly insisted that decreasing funds for Medicare or Social Security is “off the table,” Democrats and the White House have pointed to the ambiguity around his plan to suggest otherwise.

President Joe Biden speaks during the Democratic National Committee winter meeting, Feb. 3, 2023, in Philadelphia.

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

McCarthy’s comments on Monday came after he and Biden discussed the debt limit and other issues at White House last week, their first meeting since McCarthy became speaker. The sit-down yielded no commitments or outcomes, but both McCarthy and Biden described it optimistically.

“I think, at the end of the day, we can find common ground, I really do,” McCarthy told reporters in the White House driveway.

A few minutes later, the White House released its take on the meeting, saying the two men had a “frank and straightforward dialogue” and that the conversation would continue.

Both parties said no concessions were made.

Separately, top Biden administration officials have indicated that the White House will negotiate on spending and the budget in parallel talks — as long as the debt ceiling is raised without strings attached.

“One is not appropriate for negotiation; the other one is,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said Sunday on ABC’s “This Week.”

The emerging impasse echoes the 2011 debt crisis, during which the country came so close to default that its creditworthiness was downgraded for the first time in the nation’s history.

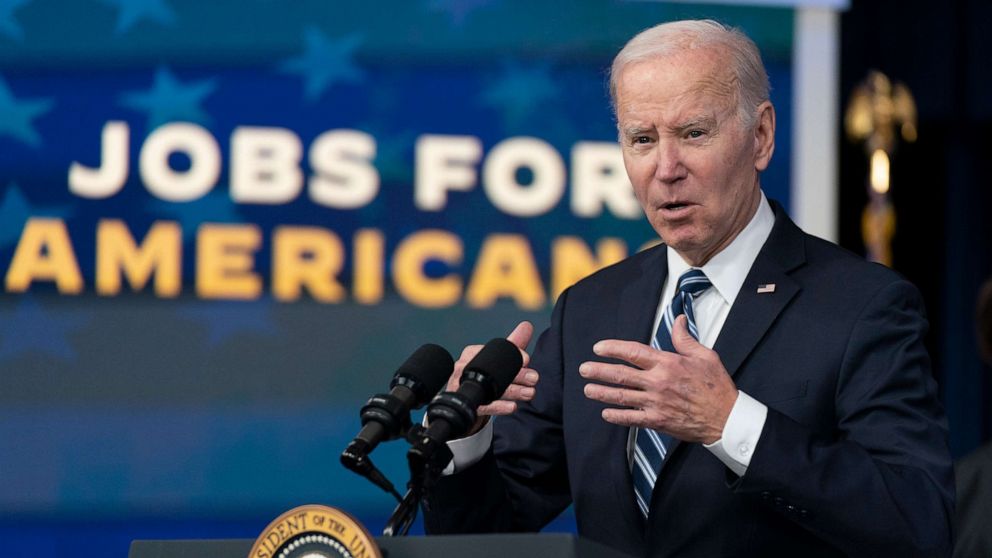

President Joe Biden speaks on the January jobs report in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building on the White House complex, Feb. 3, 2023, in Washington.

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP

At the time, the Republican-controlled House was again looking to exact spending concessions from a Democratic president.

Months before a deal, brokered in part by then-Vice President Joe Biden and Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, was passed, then-President Barack Obama addressed the nation’s debt in his own State of the Union address.

Obama called for a five-year freeze to domestic spending that would “require painful cuts” to slow ballooning debt growth.

“I’m willing to eliminate whatever we can honestly afford to do without,” he said. “But let’s make sure that we’re not doing it on the backs of our most vulnerable citizens.”